AI literacy and citizenship

In its broadest sense, literacy is the capacity to communicate with language, numbers and images and the use of those methods to understand and interact with the world. We have extended the concept of literacy to include domains such as digital literacy, financial literacy and media literacy.

But what does this have to do with citizenship? As Robinson-Pant (2023) explains, ‘All too often, the term “literacy” is used in a metaphorical sense to mean “knowledge” or “learning” (as in the phrase “emotional literacy”), thus obscuring the ways in which reading, writing, constructing and decoding diverse texts may support – or possibly undermine – citizenship.’

How do we know if the media we consume is factual and verifiable when AI can generate invented references, lifelike videos and incredibly engaging podcast discussions? Our views, politics and even our memories can be altered with tailored prompting and well created images. Understanding this is key to a functioning democracy.

Engagement with, effective use of and the ability to perform critical analysis in these realms is essential for those who want to effectively participate in today's society.

However, discussions about AI often don’t begin with practical, fact-based assessments of the technology or its capabilities. Instead, these conversations are influenced by our existing biases - cultural references rooted in mythology, folklore, and fiction. Science fiction, Asimov’s I Robot, or the Voight Kampff android test in Blade Runner for instance, serve as a common point of reference for many of us, filling in the knowledge gaps when factual information about AI is scarce.

AI literacy has been defined as ‘the knowledge and skills necessary to understand, critically evaluate, and effectively use AI technologies’ (Long & Magerko, 2020).

In the context of education, fostering AI literacy is crucial to empowering individuals to grasp how AI systems function, the potential benefits they offer, their inherent limitations, and the ethical considerations that come with their use. This concept goes beyond a superficial understanding of AI technologies, encompassing a range of competencies that include both theoretical knowledge and practical application.

AI literacy involves a foundational understanding of AI concepts, such as how AI processes data, makes decisions, and automates tasks. This knowledge is crucial for developing the ability to critically evaluate the outputs of AI systems, which may be subject to algorithmic biases and errors. Critical thinking is a fundamental component of AI literacy, enabling individuals to assess AI-generated outcomes with an informed perspective and an awareness of the technology’s limitations.

There is an ethical dimension of AI literacy too, which calls for an awareness of the broader societal implications of AI; privacy, data security, and the potential for AI to perpetuate or even exacerbate existing biases.

In addition to these cognitive and ethical components, AI literacy also entails hands-on skills that allow individuals to interact effectively with AI-powered tools and applications. AI literate citizens should be familiar with common AI technologies such as chatbots, recommendation engines, and common generative AI tools all of which are increasingly integrated into both personal and professional environments.

Improving AI literacy strengthens public voice and power, and at a basic level, we should all be equipped to understand the key concepts.

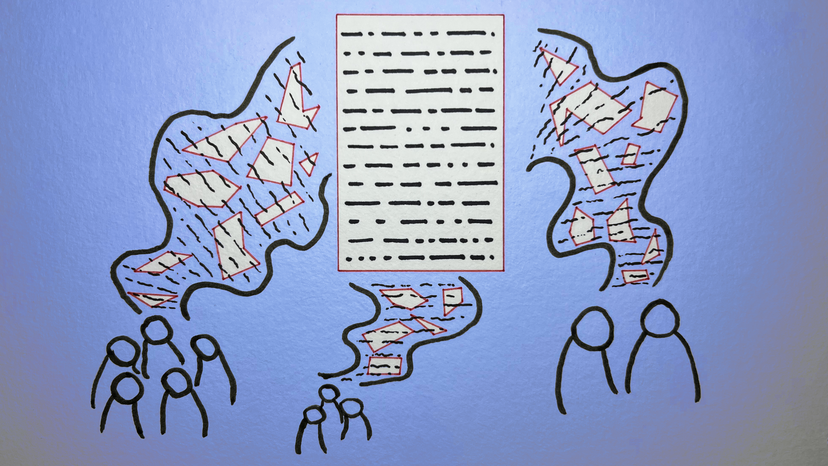

Featured Image: Yasmine Boudiaf & LOTI / Better Images of AI / Data Processing / CC-BY 4.0

https://literacytrust.org.uk/information/what-is-literacy/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666920X21000357

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10171724/

https://www.ncl.ac.uk/academic-skills-kit/information-and-digital-skills/ai-literacy/

https://www.jrf.org.uk/ai-for-public-good/we-must-act-on-ai-literacy-to-protect-public-power