Vocational teachers in the UK speak about their AI worries

The UK Jisc organisation which researches and supports Universities and Vocational Colleges with technology for teaching an learning also houses the UK National Centre for AI. They are currently undertaking Annual Surveys and producing reports on both staff and student perceptions of AI for Higher Education and also for Further Education, which includes Vocational Education and Training. This year’s report on staff perceptions was published on September 2, in time for the new college year. Sue Attewell from Jisc who was responsible for the report has written an detailed blog on the outcomes. Over the last year, she says, she has spent time with 462 staff in teaching and learning roles in colleges and universities across the UK.

The full blog is well worth reading. But I have included below the section on ‘Concerns staff are raising’. Education and training systems vary in Europe and it is noted that UK FE Colleges usually provide both General and Vocational Education as well as apprenticeships. But regardless of the differences the expressions of concern form the teachers seem to resonate with teachers I have talked to in Spain and in other European countries. I’d be interested in other peoples opinions on this.

Student use

Some staff worry that students are leaning too heavily on AI, skipping essential thinking and learning. In trades and practical subjects, this is especially concerning: you cannot rely on AI on a building site, but some learners are doing just that.

Others worry that students copy and paste multiple-choice questions into AI tools instead of engaging with the exercise. In creative subjects, there are fears about originality being lost: music staff spoke about students trying to pass off AI-generated work as their own. Across the board, staff worry about over-reliance, passivity, and loss of confidence in personal ability.

Academic integrity

There are widespread concerns about cheating. AI detectors are unreliable. Some students leave giveaway phrases like “here is the answer to your question” in their work. At the same time, staff themselves have been wrongly flagged by detection tools. This leaves many uneasy. Oral questioning is often used as a check. Some institutions send suspected cases to panels, but staff say professional judgement remains essential. Many also spoke about the moral tension of being asked to use AI in their jobs while telling students not to.

Assessment

Staff are frustrated by the slow pace of assessment reform. Many said current tasks are not fit for purpose in the age of AI. They want to design tasks that draw out critical thinking and authentic voice, but the processes take too long. At one university, staff said it took six months to change an assignment. Without greater flexibility, AI misuse will increase because outdated tasks invite workarounds.

Staff confidence

Confidence levels are uneven. Many staff are self-taught. Without clear guidance, they are unsure what is allowed, which tools are approved, or how to use them responsibly. Even where support is available, time pressures prevent staff from engaging. This fuels anxiety. Digital gaps are widening between staff and students, and between staff themselves. Some mature learners and staff struggle with the basics, while others are advanced.

Some also expressed frustration that expectations for AI use are growing, but without extra time or resource. They feel pressure is rising faster than capacity.

Ethical concerns

Bias in outputs is a big issue. One example staff shared was image tools generating racially biased depictions of criminals. Others worry about hidden human labour in AI supply chains. Transparency is another recurring theme: staff question how to ensure honesty when AI content can be indistinguishable from human work. Some raised the environmental impact of large AI systems.

Job security and curriculum relevance

Some staff fear AI could replace parts of their role. Creative and teaching staff feel especially vulnerable. Others take a pragmatic view, seeing AI as a tool rather than a threat, but all agree the landscape is shifting.

There are deep questions about curriculum. Are we still teaching the right things? Skills like composition, coding, and analysis are changing as AI takes on more tasks. Some staff fear what they teach is already becoming obsolete. Others argue the challenge is not preventing change but helping learners adapt to new competencies.

Professional identity

Many staff feel a loss of craft. Designing original resources, tailoring lessons from experience, and handwriting feedback are all being automated. This is disorienting. Without clear leadership, staff are left to make personal decisions about how much to rely on AI. They want guidance that goes beyond reassurance: clarity about priorities, role expectations, and the future value of teaching itself.

In the conclusion to her blog Sue says the staff concerns are real.

AI is already here and already shaping teaching. Staff are engaging pragmatically and creatively, often without formal support. Institutions have taken first steps with policies and working groups but there is a gap between ambition and implementation.

Staff concerns are real: fairness, relevance, workload, and professional identity. If we want AI to enhance rather than erode education, institutions must act decisively. That means aligning policy with practice, investing properly in staff, and creating cultures that support experimentation.

AI is not something on the horizon. It is already in classrooms, offices, and assessment processes. The challenge now is whether the sector can keep up.

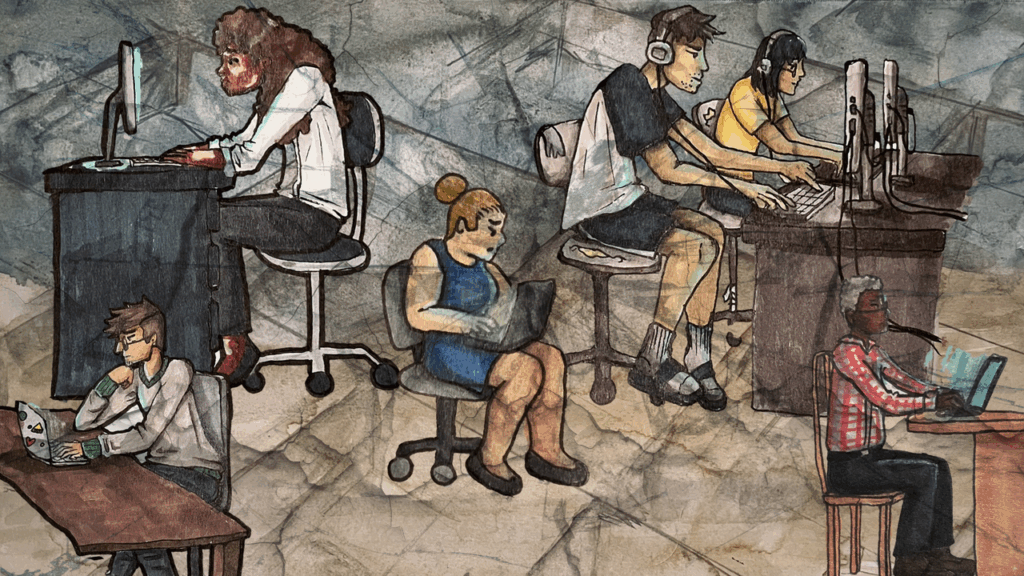

About the Image

The image is intended to represent independent data gig workers who work in isolation not only from the larger project with which they might be engaged (e.g., flagging graphic images for video platforms, tagging data for commercial AI systems or weapon systems) but also from other human workers (through distance, physical separation, or technological buffers like headphones). In the image, people at computers face away from one another and float above a painted backdrop of dim, empty cubicles, overlaid with fractured glass. This multimedia image uses a mix of traditional and digital techniques, including licensed individual pen and ink illustrations of workers by Rose Willis, a watercolor background, and public domain digital overlays by RawPixel. This image was selected as a winner in the Digital Dialogues Art Competition, which was run in partnership with the ESRC Centre for Digital Futures at Work Research Centre (Digit) and supported by the UKRI ESRC.