The Ladder, the Economy, and AI: A Deepening Debate for VET

Earlier this week, I wrote about the idea that Artificial Intelligence might be removing the first rung of the career ladder for young graduates. The piece was a reflection on the work of Alberto Romero, who argues that the automation of routine, entry-level tasks is creating a long-term talent pipeline crisis. It is a narrative that is worrying many of us in education and training as we are fundamentally in the business of helping people get onto that very ladder.

However, the conversation around AI is never simple, and a counter-argument has emerged that challenges this narrative. In a recent paper titled “Looking for the Ladder,” Zanna Iscenko and Fabien Curto Millet from Google’s Chief Economist’s team suggest that we may be misdiagnosing the problem. While acknowledging the very real difficulties facing young people in the current job market, they propose that the culprit is not AI, but a more traditional economic force: the sharpest cycle of monetary policy tightening in four decades.

Their argument is grounded in a critical examination of the timeline. The narrative of AI-driven job loss often points to the public release of ChatGPT in November 2022 as the starting gun. Yet, Iscenko and Millet show that the downturn in hiring for the most “AI-exposed” occupations, such as software engineering, began much earlier, in the spring of 2022. This timing aligns perfectly with the start of aggressive interest rate hikes by central banks, a classic economic lever that historically cools down the very sectors—tech and finance—that are now considered most exposed to AI. Their analysis suggests that what we are seeing is not a new wave of technological displacement, but a familiar pattern where interest-rate sensitive industries pull back on hiring, and young workers, who are most dependent on new job openings, are hit the hardest.

This perspective introduces a healthy dose of skepticism, particularly given the authors’ connection to Google, a major player in the AI field. It is a reminder that we must critically examine the data and the narratives built upon it. The authors argue that the rapid, widespread replacement of junior staff by AI within months of a consumer chatbot’s release is simply implausible. Corporate adoption of new technologies is a slow, complex process, and the enterprise-grade AI tools that could genuinely replace workflows were not even available when the employment decline began. Instead, they suggest that the focus on a narrow age band of 22-25 year olds can create a statistical illusion, where a general hiring freeze mechanically shrinks the youngest cohort as new graduates are not hired to replace those who age out of the bracket.

This debate is of profound importance for the vocational education and training community. It is not merely an academic squabble over economic data; it cuts to the heart of how we prepare learners for the future. If the primary challenge is a cyclical economic downturn, then the policy responses and educational strategies might focus on resilience, career guidance through economic cycles, and strengthening work-based learning to provide a foothold even in a tough market. If, however, the challenge is a fundamental, technology-driven restructuring of work, as Romero suggests, then VET would need to undertake a more radical transformation, focusing on the cultivation of tacit knowledge and the meta-skills that AI cannot replicate.

Perhaps the most valuable lesson from this exchange is that the world of work is not being shaped by a single force. It is a complex interplay of technological innovation, economic cycles, and corporate strategy. For VET practitioners, this means we must resist the allure of simple narratives, whether they are of utopian transformation or dystopian collapse. Our role is to equip learners with a dual form of adaptability: the skills to navigate the immediate realities of the job market, whatever the economic weather, and the critical, creative capacities to thrive alongside the powerful new cognitive tools that are becoming part of our world.

The discussion reminds us that our focus should be on developing robust, evidence-based understandings of labour market changes. It highlights the enduring value of the apprenticeship model, not as a nostalgic throwback, but as a sophisticated mechanism for developing the deep, embodied knowledge that remains uniquely human. As we move forward, the challenge for VET is to hold these competing perspectives in view, to prepare learners for a future that will be shaped by both economic tides and technological waves, and to ensure that the ladder of opportunity, in whatever form it takes, remains accessible to all.

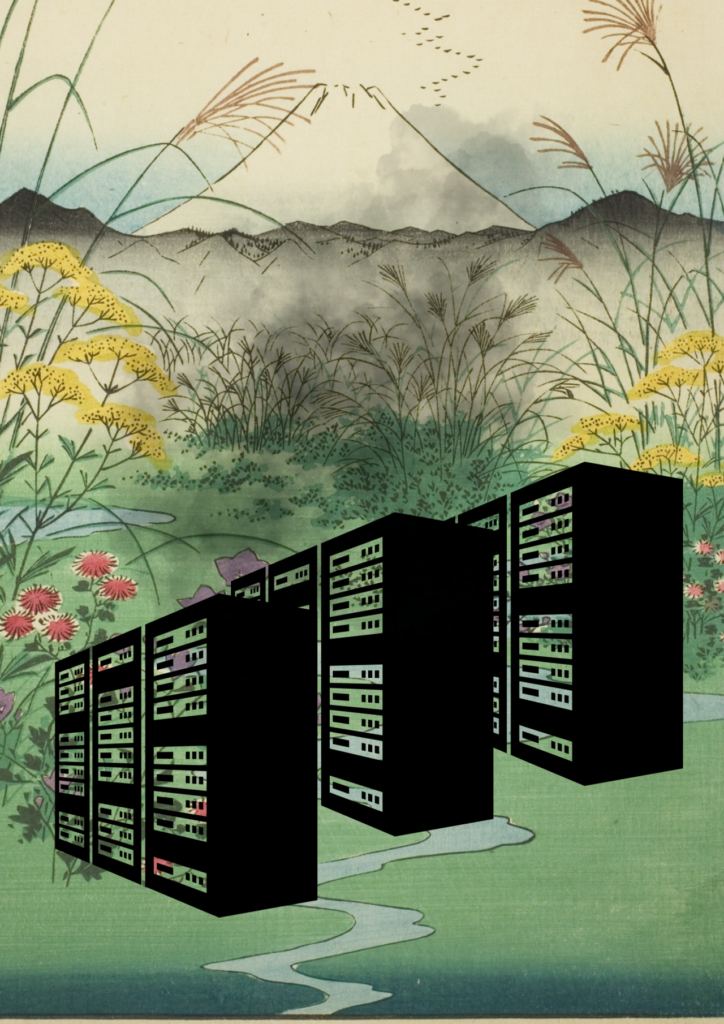

About the Image

This image shows multiple data servers located in a beautiful landscape but emitting a dark cloud of smoke. It demonstrates the impacts of data centres on the natural world through pollution emitted from the operation of the centres. The image was inspired by my research on the environmental impacts of data centres built around the world to service the expansion of GenAI. I found the image of the landscape (Japanese) on Public Work by Cosmos and used Canva to complete the image.