How can we develop the European Technology industry?

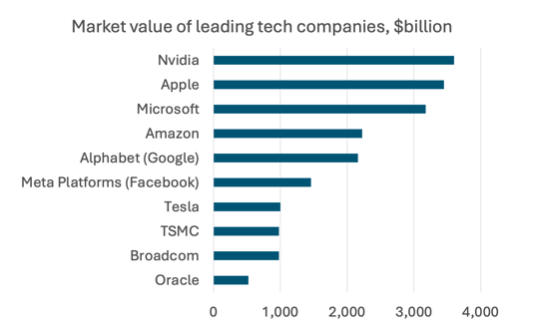

Look at a list of the ten tech companies with the highest market valuation as of mid-November. With the exception of the Taiwanese semiconductor giant TSMC, all are American; no European company even comes close.

In an article entitled Why Does U.S. Technology Rule? in his new (free) newsletter, Krugman Wonks Out, renowned economist Paul Krugman examines the reasons for such American domination. Krugman points out America is a big country, “yet our tech giants all come from a small part of that big nation”. Six of the companies on the list are based in Silicon Valley, he says, and while Tesla has moved its headquarters to Austin, it was Silicon Valley-based when it made electric cars cool and the other two are based in Seattle, which is sort of a secondary technology cluster.

Yet discussion and to an extent policy direction has focused on things like excessive regulation in Europe, a financial culture that is not willing to take risks and so on. This is the reason often cited for American large companies dominating the development of AI.

Krugman goes on to say:

I’m not saying that none of this is relevant. But one way to think about technology in a global economy is that development of any particular technology tends to concentrate in a handful of geographical clusters, which have to be somewhere — and when it comes to digital technology these clusters, largely for historical reasons, are in the United States. To oversimplify, maybe we’re not really talking about American tech dominance; we’re talking about Silicon Valley dominance.

He ascribes European lower historic levels of G.D.P. per capita than the United States, to shorter Europeans working hours, including mandatory holiday pay, “while America was (and is) the no-vacation nation.” Europeans had less stuff but more time, he says “and it was certainly possible to argue that they were making the right choice.”

Indeed he goes on to say that analysis shows that excluding the main ICT sectors (the manufacturing of computers and electronics and information and communication activities) , EU productivity has been broadly at par with the US in the period 2000-2019.

Besides technology, the US also has high productivity growth in professional services and finance and insurance, reflecting strong ICT technology diffusion effects.

Industrial clusters have a key impact in developing and exchanging knowledge as happened in the past in the cutlery industry in Sheffield, “but the same logic, especially local diffusion of knowledge, applies to tech in Silicon Valley, or finance in Manhattan:”

Krugman concludes by asking two big further questions.

First, to what extent does high productivity in a few geographical clusters trickle down to the rest of the economy? Second, is there any way Europe can make a dent in these U.S. Advantages?

This article caught my attention because in the end of the last century there was a big discussion about the role of industrial clusters in Europe. Cedefop published a book focusing on knowledge, education and training and clusters for a European US conference held in Akron.

I’ve finally managed to find a digital copy of the book and will summarise some of the ideas. But a big question for me is if and how policies at a national and regional level can support the development of regional industrial clusters in Europe and what impact this might have in developing knowledge in key sectors including technology and AI. What can we do to make such knowledge clusters happen?